There’s a photograph on a wall in Eldorado Park. In it, a man stands in front of a mint-green BMW E30, hands in his pockets, a thick gold chain resting just above a crewneck T-shirt. It’s the late ’90s. The paint on the Beemer is still fresh. His smile’s half-cocky, half-proud. But ask around, and no one can quite agree what happened to that gold chain. Some say it was pawned when times got tough. Others say it was passed on to a younger cousin. And a few believe it’s still tucked away in a shoebox under someone’s bed, waiting for the next family wedding or funeral.

That quiet uncertainty, that mix of permanence and disappearance, says a lot about how gold jewellery lives and dies in South Africa’s townships. Unlike in the high-gloss pages of luxury magazines where gold is frozen in display cases or bank vaults, here it moves, it changes hands. It doesn’t always stay where you expect it to.

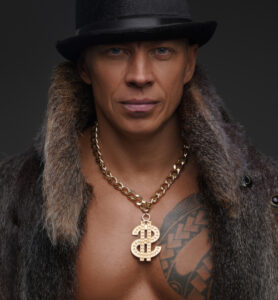

In places like Soweto, Mitchells Plain, and Umlazi, gold chains aren’t just accessories. They’re signals. Status. Survival. Memory. You can walk into a tuck shop on any given afternoon and see a teenage boy wearing his first slim rope chain, bought with money saved from weekend shifts. Or you’ll spot an older man at the taxi rank, his heavier Cuban link glinting in the sun, weathered by years of wear.

But what’s really interesting isn’t just the gold’s presence, it’s what happens after.

When someone passes, for instance, the question of who inherits a chain can carry more weight than who gets a piece of furniture or a car. It’s not about financial value alone. It’s about who’s next in line to carry the story.

In many township families, gold chains are handed down like heirlooms, especially during significant rites of passage, an 18th birthday, a wedding, or, just as often, a funeral. Sometimes that chain becomes a kind of unofficial family emblem, a quiet thread tying together different generations who maybe never met but share the same piece of metal against their chest.

There’s also an undeniable layer of practicality woven into this tradition. Gold, as anyone from Joburg to Khayelitsha will tell you, is liquid wealth. If hard times hit, that chain can cover a rent payment or school fees. Pawn shops in these areas aren’t just about gambling losses, they’re also quiet banks for communities who don’t always have access to formal credit. You bring in a chain, get some cash, maybe buy it back when things level out.

That duality, jewellery as both treasure and transaction, makes gold chains something more complex than just bling. They’re both symbols and tools.

Walk through Carlton Centre in Johannesburg or the buzzing jewellery stores around Durban’s Warwick Junction, and you’ll find countless shops selling pre-owned chains. Some come with paperwork. Many don’t. But every link has likely had a life before the one it’s about to begin again. A chain bought for a matric dance might end up years later around a new neck, in a new city.

This cyclical nature adds an unspoken layer of humility to the glamour. Unlike high-end watches or designer handbags, gold chains here aren’t frozen in status, they shift, lose shine, get polished again. They’re lived in.

Of course, there are risks to this culture. Chain snatching is real. Street crime in places like Hillbrow or parts of Cape Town has given rise to a local saying, “If you’re wearing gold, you’re wearing a target.” But still, the chains stay visible. They keep getting worn. That says something about how deep the relationship runs, how people value the signal enough to take the risk.

Of course, there are risks to this culture. Chain snatching is real. Street crime in places like Hillbrow or parts of Cape Town has given rise to a local saying, “If you’re wearing gold, you’re wearing a target.” But still, the chains stay visible. They keep getting worn. That says something about how deep the relationship runs, how people value the signal enough to take the risk.

There are also quieter moments, away from street corners or Sunday church services, where gold’s afterlife plays out. At family gatherings. At kitchen tables. An elder polishing a chain before giving it to a grandson. A cousin trying on a heavy piece for the first time and feeling, in that small but tangible way, that they’ve inherited more than just metal, they’ve inherited belonging.

That’s the real heart of it, gold as connection.

Not long ago, I spoke to Thuli, a 42-year-old nurse from Katlehong. She still wears her late father’s chain every day under her scrubs. “He bought it when I was in primary school,” she told me. “When he passed, it didn’t feel right for it to just sit in a drawer.” It’s not flashy. It’s not thick. But it’s there, a hidden reminder of where she comes from, tucked just beneath her collar.

That kind of quiet legacy repeats itself across the country, untracked by statistics or fashion blogs. In townships and suburbs alike, gold chains flow through hands and hearts, turning from status symbols into family artefacts.

In the end, the afterlife of gold chains in South Africa’s townships isn’t really about wealth. It’s about memory made solid. It’s about something you can touch when the people who bought it are gone, and something you can pass on when your own time comes.

So maybe that chain in the photograph, the one with the man and the mint-green BMW, never really disappeared. Maybe it’s just waiting for the next moment, the next wrist, the next quiet ceremony when someone pulls it out of a box, dusts it off, and drapes it back around their neck, carrying all those years with them in a single, simple weight.